No matter the season, when I was a kid and my family took a trip to Frankenmuth, Michigan, we always made a stop at Bronner’s, where it’s Christmas all year round. Straight on through the doorway and veering slightly to the immediate right brought you to a show floor full of decorated Christmas trees, towering to the ceiling. As I remember them they were largely of the aluminum variety, in every off-color imaginable: magentas and silver, greens that corresponded to nothing in nature. Even the icicles of tinsel were gaudy to my young eyes (tinsel being verboten in my household because it was considered overkill by my parents’ sensibilities). I was eager to move on as soon as possible to find another unlikely character figurine to add to an already crowded nativity scene (the choices seemed without limit: there were water carriers, bread makers, musicians and even an elephant).

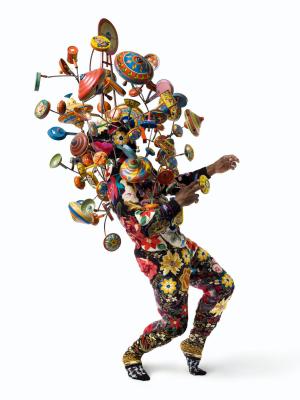

The vivid memory of that indoor forest came rushing back upon entering Yerba Buena’s exhibition of Nick Cave’s Soundsuit creations, many of which reach altitudinous heights. If there was any sign of my jaded childhood self amongst the visitors, I missed it: the kids in the gallery seemed absolutely agog at Cave’s wild creations, which are fitted to mannequins standing on platforms, set in an a nearly intersecting X-formation, in the center of the room.

The costumes of Meet Me at the Center of the Earth show influence of the ceremonial garb of many world cultures, but they also display a keen eye for taking the most unpretentious and even (dare I say) vulgar of articles and constructing something beautiful from them. After all, here are the baskets that began appearing like clockwork every Christmas when my grandmother succumbed to a beaded plastic phase, the ones my sister and I would hide behind any bit of decorative screen available before guests arrived. I wish she was visiting now so I could point them out and she could shoot me a triumphant look of confirmation.

Attached like barnacles are potholders and knitted caps, God’s Eyes and plastic blossoms. Stretched over the shape of a polar bear frame are Aran Sweaters. One suit sports metal perches for porcelain birds, giving the appearance of a wearable candelabra. A tall polka-dotted feather duster looks ready to spring from the platform, an over-sized moldy bag of mobile Wonder Bread waiting to be set loose on an unsuspecting public. Like a fungal forest, another is covered with jutting brightly colored toys: tops and noise makers and rattles.

Eventually, a line of shaggy pom-poms come into the room as the day’s performance gets under way. The dancers are wearing costumes less elaborate than those on display but which allow them more freedom of movement. Their rustling procession seems to bring a hush of calm to we visitors a bit blissed out by the visual overload of the exhibit. What starts as the quiet percussion of brush on drums eventually becomes a loud and well choreographed group dance after the performers snake their way back into the side gallery near the stairs. I was a bit disappointed at first that I didn’t get to find out what, say, the sound of a suit-clad stroller with an abacus face mask sounds like. But the recital eventually won me over, even crammed as we were in that tight space. It was also rather humbling to find a profusion of cringe-inducing signifiers of my childhood, the lost articles of hundreds of flea market trips, making a star appearance, as if to say, this is what we were waiting for all along.

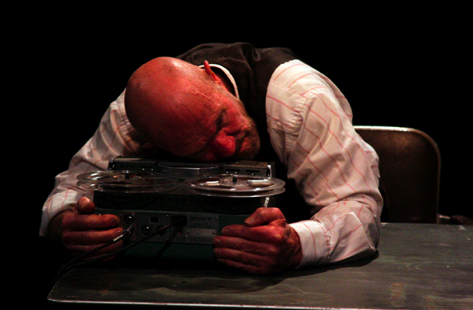

Kentridge moves the action of the Prologue to an operating theater. As the musicians look on from the raised tier above, Time, Fortune and Love examine the huddled form of Ulysses on his bed, employing a pointer to delineate the many sufferings he has endured during his travels. Ulysses, represented by one of the nearly life-sized wooden puppets, barely stirs beneath his bedsheet. The accompanying projection on a screen above interweaves animation of the ills the flesh is heir to with actual footage from medical videos: disquieting glimpses of organs being probed and journeys through quivering canals. So in actuality Ulysses is somewhere betwixt the two states hinted at by the stage and screen: hospitalized but perhaps barely clinging to life.

Kentridge moves the action of the Prologue to an operating theater. As the musicians look on from the raised tier above, Time, Fortune and Love examine the huddled form of Ulysses on his bed, employing a pointer to delineate the many sufferings he has endured during his travels. Ulysses, represented by one of the nearly life-sized wooden puppets, barely stirs beneath his bedsheet. The accompanying projection on a screen above interweaves animation of the ills the flesh is heir to with actual footage from medical videos: disquieting glimpses of organs being probed and journeys through quivering canals. So in actuality Ulysses is somewhere betwixt the two states hinted at by the stage and screen: hospitalized but perhaps barely clinging to life. Garnica began with her body wrapped into a tight ball, until finally her feet dug into the thin layer of chalk on the stage, propelling herself in a slow circle. Leaning forward into an uncomfortable looking position balanced on her shoulders, her tensed arms began to repeat several compulsive gestures, hands meeting and separating as though stretching out a piece of taffy, and then obsessively knocking on the stage or upon the air. After stretching both legs toward the ceiling and holding for an ungodly amount of time, the performance accelerated as she worked her body into a standing position, her hair enveloping her head like a burial shroud. When later she cast a long searching gaze upon the audience, the effect was startling. What had preceded it seemed more some kind of shamanic trance than an act of will. Still later she leapt from the stage, scattering clouds of chalk dust as she shook in place before circling the room in a dance of alternately jarring and graceful steps.

Garnica began with her body wrapped into a tight ball, until finally her feet dug into the thin layer of chalk on the stage, propelling herself in a slow circle. Leaning forward into an uncomfortable looking position balanced on her shoulders, her tensed arms began to repeat several compulsive gestures, hands meeting and separating as though stretching out a piece of taffy, and then obsessively knocking on the stage or upon the air. After stretching both legs toward the ceiling and holding for an ungodly amount of time, the performance accelerated as she worked her body into a standing position, her hair enveloping her head like a burial shroud. When later she cast a long searching gaze upon the audience, the effect was startling. What had preceded it seemed more some kind of shamanic trance than an act of will. Still later she leapt from the stage, scattering clouds of chalk dust as she shook in place before circling the room in a dance of alternately jarring and graceful steps.