In the spirit of the 4 Star, the best movie house on Earth, I thought I’d combine two reviews into one ass-kicking double feature. You’ll have to provide your own shrimp chips and popcorn yeast of course.

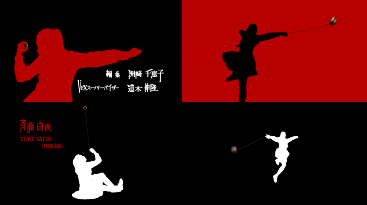

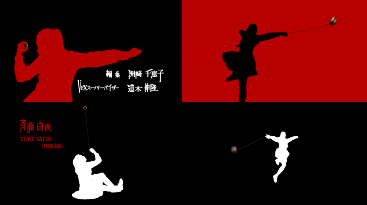

Let’s get this out of the way, right off: Yo-Yo Girl Cop has the best opening credit sequence ever made (Saul Bass fans clam up).

Out of the public eye, a select number of teens are tapped to go undercover to infiltrate schools where domestic terrorist threats are suspected to be hiding. Other than their wits, empathy for their peers, and whatever fighting skills they might have accrued in their past lives (the girls seem by nature or nurture to be a pretty brutal bunch), their weapon and sole identifier as a member of the elite group is their yo-yo.

It’s always fun to see what other countries can do with what is largely an American concept: super heroes. It was British writers who added much of the polish and depth that we expect nowadays from characters who for decades were content with looking colorful and engaging in what amounted to schoolyard brawls that tore up city blocks. The Philippines gave us Gagamboy, which while often funny, came off more as a parody than a serious contender. Cutie Honey from Japan cranked up the humor still more, which unfortunately made the outing seem to sag a bit when the character had to get down to the business of saving the world (yet, still a favorite all things considered).

Yo Yo Girl Cop plays it with a straight face. Sort of. If there is one thing in common I love about so many Japanese films, it’s the sincerity. Faced with the alarming number of suicides among teens or the disaffection of the hikikomori, for a country that often identifies restraint as part of the national character their cinema displays an outpouring of sympathy for adolescents and the trials they face. The film is honest enough to admit that adults for the most part don’t have a clue how their kids are feeling. So we get quite a bit of Aya Matsuura as Saki Asamiya simply dealing with the problems of both bullying and suicide chat rooms while investigating the school.

Where Gagamboy never missed a chance to wink at the audience, Yo Yo Girl Cop rarely does, but although Saki Asamiya’s initiation into the life of an undercover operative takes a page right out of La Femme Nikita, there is nothing nearly that sublime here. It skews closer to Spider-man where things are deathly serious, but there’s time out now and again for a few laughs from J. Jonah Jameson. Here we get Riki Ishikawa as her minder, pulling faces every chance he gets, and I like him more and more with every sneer. There are certainly plenty of over-the-top performances to go around, perhaps all the more endearing since everyone seems so earnest you can’t help but feel that they’re all quietly dancing around the silliness of the central conceit of the main character’s arsenal. It’s important to remember that super heroes as a concept are inherently pretty ridiculous to begin with. You’re going to have to wait ’til the very end for the yo-yo fight. It’s brief, but believe me it’s worth it.

Madam City Hunter, on the other hand, doesn’t even bother with a prolonged title sequence. Before you can say in media res the bullets are flying and our heroine is on the scene. This is the kind of lean and mean storytelling that Hong Kong brought to action films decades ago that made American films taste like weak tea by comparison. Alas, some of us had to play catch up, and it’s clear that by the Nineties when this film was released, the formula had been refined to perfection. Thankfully, Hong Kong directors, perhaps because of the huge numbers of films released each year and anticipating their audiences ever sharpening appetites were never willing to rest on their laurels. There was still a lot of experimentation going on, seeing just how much you could alter the ratio of comedy to drama for example, or just how you could do a shoot-out sequence a little differently.

In the case of Hunter, we get an increase to the humor quotient, which if graphed would look like a continual ascent with brief dips appearing for the occasional action set piece. Although martial arts films frequently mix comic elements during frantic fight sequences, Hunter is constantly deflating suspenseful set-ups with a humorous denouement. It’s as though the main characters just can’t take the situations they’ve been placed in seriously. So when an assassin slips into an apartment, turns on the gas and plants his bomb, the protagonists tweak to it pretty quickly, but spend most of the time bickering over who is going to deal with the problem. It’s almost as if they’ve disarmed the set-up rather than the bomb.

So who is Madam City Hunter? She’s Cynthia Khan, playing Yang Ching, the toughest cop on the force. Yes, like every cop in film since time immemorial she falls under scrutiny and is nearly pulled from the case, but in a refreshing HK twist, her superior begs her to cross the line and do things her way (it may have something to do with the fact that he’s developed something of a crush on his subordinate).

Joining her as partner is a private investigator played by Anthony Wong. If I’m not completely mistaken his character is actually named Charlie Chan. He provides a little approximation of a broken English stereotyped Chinese character at one point for laughs, which was so unexpected and daring that I think I yelped. I’m so used to seeing this guy in hard boiled roles like in Beast Cops and Infernal Affairs that it’s nice to see him making mince meat out of a comic role. He also sports a shaggy mane of scraggly hair in this one, which means some terrible looking wigs on the stunt men.

Shelia Chan plays Charlie’s love interest Blackie, who from the moment she appears pretty much steals the show. If IMDB is to be believed it’s unconscionable that she doesn’t have a filmography as extensive as Wong’s. Along with the police chief, they together form a kind of Love Quadrangle, everyone suspicious of the other’s affections. The brilliance behind it is that it’s all just Charlie jerking everyone else around to amuse himself. One scene in a restaurant finds all of the characters speaking in voice-over wondering about the others’ intentions while reading all kinds of meanings into every move of a chopstick. Blackie, worried that Charlie is falling for Yang Ching, gets progressively drunker, punctuating every exchange between him and the chief with yet another toast, with predictable results.

So what do you get for your rental price? You get a battle on bamboo scaffolding. A cool set piece fight on a dam. There is the dreaded “Wonder Strike,” mentioned more often than performed. There’s a car wash seduction scene, a dinner seduction scene, a haircut seduction scene, all of them played thankfully for laughs. There is the fun that only decades-old movies can provide of revealing what filmmakers thought would be a cool apartment (red brick wallpaper), a cool club (neon sign of a music stave with blinking notes), or a bad-ass gang hideout (lots of graffiti in day glo colors of big Rolling Stonesesque lips, skulls and peace signs). It’s unconscionable that this didn’t go into sequel mode á la the Mad Mission series. Some people aren’t fond of the admixture of comic, romance, drama and action but Hong Kong cinema does it oh so well, so if you’re game, here’s an antidote for those deathly serious action films that do none of the above well at all.

In the shadow of Mount Fuji, a drifter spins a tale about a hidden cache of gold left behind in a town that was once the battleground between two warring clans. That town just happens to be in Nevada, and the drifter is a sharp shooter played by none other than Quentin Tarrantino, so you know right off the bat that you’ve entered Takashi Miike territory.

In the shadow of Mount Fuji, a drifter spins a tale about a hidden cache of gold left behind in a town that was once the battleground between two warring clans. That town just happens to be in Nevada, and the drifter is a sharp shooter played by none other than Quentin Tarrantino, so you know right off the bat that you’ve entered Takashi Miike territory.  It was fortuitous that recently I was able to

It was fortuitous that recently I was able to