The reader of The Classic of Mountains and Seas plays hopscotch from peak to peak, moving in leaps and bounds roughly according to one of the four cardinal compass directions. On each stop the traveller is given a Rough Guide equivalent of the major points of interest: natural resources, resident deity, flora and fauna. Some of the denizens are rather strange. A familiar creature may be used as reference for point of comparison, but deviations from the expected are dutifully noted: a multiplicity of legs, a single eye, a human face atop a snake’s body.

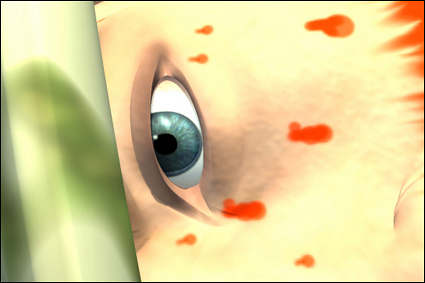

None are perhaps as strange as the “look-flesh” creature, helpfully described by translator Anne Birrell in the glossary of the Penguin Classic edition, quoting third century commentator Kuo P’u, as “a mass of flesh which looks like the liver of an ox: it has two eyes.” Coming across it again and again in the text, I’ll admit I found it rather hard to visualize hopping about the slopes of its territory. Farther east than the scholars could have imagined (and their imaginations were robust), further even than the country of the Blacktooth people across a vast ocean is a city at the foot of two hills, barely worthy of mention compared to the legendary peaks in the eighteen books. I only bring it up it because it’s here that I think I’ve finally got a glimpse of the “look-flesh,” far from its home.

Liting Liang is only one of the dizzying number of participants in the Chinese Culture Center’s current show Present Tense Biennial. Her ink on paper works immediately brought to mind the descriptions from the book (one of the joys of which is the many interpretations by artists throughout the ages of the creatures within). There is the crouched chimerical woman, lower body sheathed in rows of reptile scales. Another figure stands posed, cleaver in hand, snake wrapped around her neck like an alert scarf (snakes are often described grasped in the hands of deities or clamped between their jaws). Then there’s a curious lump of a thing, kind of like a potato or blowfish with legs, in stockings and heels. Is this the “look-flesh,” dressed to impress for the twenty-first century? It’s probably wishful thinking. Maybe a distant relation? Or is it something never before seen, field notes for an as yet unwritten nineteenth book? At the very least, the impossibilities inherent in her striking work offer a good entrance point for the show as a whole, because it gives me license to call her a favorite among a multitude of favorites in this diverse and absorbing show (a site dedicated to images from the center has proved a broken link in the last few weeks that I’ve tried to visit. But you can get an idea of how amazing her pieces are here:, it’s the first image in the review).

The bulk of the show is less concerned with mythology as a whole as it is with mythologizing, or to be more specific demythologizing. Curator Kevin Chen of Intersection for the Arts, with the aid of Abby Chen and Ellen Oh, have spread the net wide in the selection of contributors: 31 artists, not all of them of Chinese origin or descent. The diversity of the participants has borne fruit in a show with varied approaches and executions. I start with Liting Liang’s work not just because I love her ravenous eater and dismembered legs washed ashore but because the works are so singular. The raison d’être of the show has such a strong psychological pull that it’s easy to forget that Present Tense is not just an exercise in itself. The show offers many reminders that identity is a tricky thing, constantly embattled and contentious, and many of the pieces are meditations on that theme, urging the viewer to revise their assumptions. But the engine that drives that process is the uniqueness of each artist’s vision: they are well worth appreciating each for their own sake.

Thomas Chang, for example, explores what’s left of a theme park in Orlando, Florida fallen into disrepair. The miniature monuments captured in C-Prints have a haziness in the details which only serves to draw attention to the haziness behind the enterprise itself. The brain child of the Chinese government, the amusement site was meant to foster interest in tourism with replicas of famous sites in 1/10th scale. A facsimile of Tengwang Pavilion however is now gutted, the front exposed like a doll house and overgrown with weeds. This official “imprimatur” of Chinese culture, made for export and based on sites of historic importance and grandeur, has an interesting counterpart in the export of Americaness in Charlene Tan’s work (more on that in a bit).

Thomas Chang, for example, explores what’s left of a theme park in Orlando, Florida fallen into disrepair. The miniature monuments captured in C-Prints have a haziness in the details which only serves to draw attention to the haziness behind the enterprise itself. The brain child of the Chinese government, the amusement site was meant to foster interest in tourism with replicas of famous sites in 1/10th scale. A facsimile of Tengwang Pavilion however is now gutted, the front exposed like a doll house and overgrown with weeds. This official “imprimatur” of Chinese culture, made for export and based on sites of historic importance and grandeur, has an interesting counterpart in the export of Americaness in Charlene Tan’s work (more on that in a bit).

Across the room, Imin Yeh’s Good Imports, 2008 presents a laptop completely shrouded in patterned textile. In an online interview, the artist explained that the fabric is typical of that found lining boxes of souvenirs from China. Perhaps it is the usual taboo of “look but don’t touch” but the wrapping evokes a sense of prohibition at the sight of screen and keyboard enveloped, even while the design lends a mystique of value, despite both the material and the hardware being the result of mass production. There is a divide between the reaction to goods which reach our shores somehow imbued with a sense of China as a country of deep history and traditions and cheap consumer products whose cheapness would not be possible were they made State-side.

Exploring the source of those imported goods whose provenance is invisible to most consumers, Suzanne Husky recreates a factory floor of tiny workers. As a group they are nearly indistinguishable in their spread armed poses and blue aprons, but the faces are taken from photographs of actual people, giving at least the illusion of individuality. Down on Kearny St., Husky has installed a sister piece in an empty store front that instills the eerie sensation of spying on actual factory workers through the glass doors (see below).

Exploring the source of those imported goods whose provenance is invisible to most consumers, Suzanne Husky recreates a factory floor of tiny workers. As a group they are nearly indistinguishable in their spread armed poses and blue aprons, but the faces are taken from photographs of actual people, giving at least the illusion of individuality. Down on Kearny St., Husky has installed a sister piece in an empty store front that instills the eerie sensation of spying on actual factory workers through the glass doors (see below).

The portraits in Sumi ink by artist Nancy Chan are precisely observed. The sense that Annie is observing you above her clasped hands is palpable. The works were rendered on long sheets of paper calling to mind traditional prints and calligraphy presentation.

I’m watching Fang Lu’s music video Straight Outta HK when I see a familiar face. Alex Yeung is the front man of hardcore band Say Bok Gwai (and a coworker of mine) and the story behind the piece is coaching hip hop artist Kelda in a cover of one of their tunes, the trick being the lyrics are in Cantonese.

Perhaps the most dramatic piece in the show is the cornucopia built of wire and paper, spilling out facsimile cartons of McDonalds packaging. The name of the piece, The Good Life, 2009 reminds us of the associations that accrue to the powerhouse chain’s product, being such a ubiquitous American brand. But a close look at the photocopied boxes reveal the traces of glocalization. These particular boxes have been tailored for the Chinese market, while still retaining the signifiers (like the arched “M” logo) that entice a consumer hungry not just for food but the array of symbolic connotations that go along with it. Charlene Tan’s piece captures many of the absurdities: the ostensibly American meal would be prepared and served by Chinese workers employed by the franchise, and even the most American of offerings on the menu go through a process of vetting to make sure they’re attractive to the palates of the country of that particular outlet. The abundance of empty boxes inside the horn of plenty underscores that our exported idea of “the good life” may not be all it’s cracked up to be. Even the “weave” of the cornucopia is just a photocopied texture.

Fans of painted chopsticks, bundled in groups of a hundred, form Arthur Huang’s demographic study of cities in which he has held residence. My Life as a Chinese American So Far (36 Years and Counting), 2009 breaks down the racial makeup of communities based on census data. Simply looking over the color key (“raw umber” for African Americans, “burnt sienna” for Latino Americans) reveals the quixotic nature of the enterprise. Huang has attempted to match the selected hues with an eye to them reflecting to some degree an approximation of actual skin color. In doing so he underlines the suggestive power of what appears at first glance to be objective statistical data. Even the selection of something as subtle as color coding can have a profound effect on our assumptions whether we are aware of it or not.

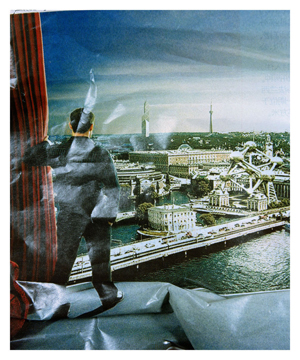

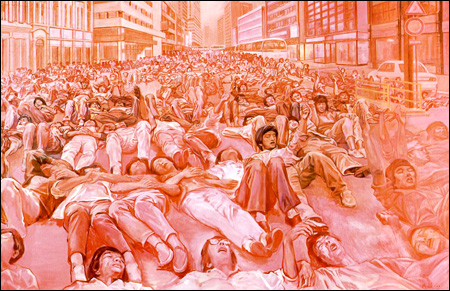

Yu Yudong’s One person’s parade series is a good end point for this glimpse of a show that negotiates ideas of shared heritage, tradition and experience even while critical of imposed collective identities. The four protest signs display photographs of the artist, bullhorn pressed to his mouth, sign in hand. In one, he stands in an empty street, midway between a crosswalk, beneath signage indicating that this is the city of Songzhuang, China. In another, he is atop a wall of painted brick, near the building’s corrugated metal roof. The works stand in stark contrast to the work of Hei Han Khiang just a few rooms away that focuses on the Tiananmen Square protests of Spring 1989. Although following the forms of the demonstrator engaged in a group action, Yu Yudong’s “protester” stands alone with an unknown message that goes unheard, at times in locations where his presence is assured to go unnoticed.

The Present Tense show actually continues outside the gallery, with a number of satellite installations located throughout Chinatown on Kearny St., Clay St., Columbus Ave. and Walter U. Lum Place. You can watch video of curator Kevin Chen touring a few of the window displays on this installment of Culture Wire.

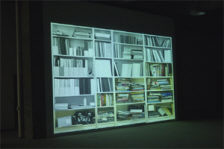

Passing back through the curtain and taking a seat it’s a while before it dawns on me: down in the lower left hand corner, one book at a time, the spines of the volumes are being whited out. It’s a little like watching the whitewashing of graffiti or the painting of a wall but somehow way more absorbing. It delivers that satisfactory sensation of completeness, the promise that each book will get the same treatment as the last in the process.

Passing back through the curtain and taking a seat it’s a while before it dawns on me: down in the lower left hand corner, one book at a time, the spines of the volumes are being whited out. It’s a little like watching the whitewashing of graffiti or the painting of a wall but somehow way more absorbing. It delivers that satisfactory sensation of completeness, the promise that each book will get the same treatment as the last in the process.

Nguyen Mahn Hung’s fighter jets with their incongruous payloads of cereal goods and pig carcasses in Go To Market, 2004. The F-4 Phantoms are contemporaneous with the Vietnam War. The appearance of the later F-18 Hornet suggests the enduring legacy of the co-mingling of commerce and militarism (UPDATE – or not, check out Johnny O’s correct identifications in the comments. Thanks again!). It’s a striking image of the disparity between humble and humbling levels of technology that prompts no end of reflection. Who gets to own which? Who’s in charge and why? How do we get there from here and what will become of us if we do?

Nguyen Mahn Hung’s fighter jets with their incongruous payloads of cereal goods and pig carcasses in Go To Market, 2004. The F-4 Phantoms are contemporaneous with the Vietnam War. The appearance of the later F-18 Hornet suggests the enduring legacy of the co-mingling of commerce and militarism (UPDATE – or not, check out Johnny O’s correct identifications in the comments. Thanks again!). It’s a striking image of the disparity between humble and humbling levels of technology that prompts no end of reflection. Who gets to own which? Who’s in charge and why? How do we get there from here and what will become of us if we do?

Ranger Circle, 2007 by Simon Gush is a slow pan in snapshots that dissolve into each other of man on a horse in the tall grass that reminded me of the more solid memorials on plinths around the world dedicated to those who generally spent their life running down others on horseback with saber and rifle. Struggles of the Heart, by Churchill Madikida shows the artist’s face in close-up, covered in white paint as he shovels handfuls of gruel into his mouth. At some point it became apparent that the film was playing in reverse, or had it always been? As he slurps the paste, nearly choking, more of it comes leaping into the frame from below into his mouth. His eyes are pressed tightly closed in concentration and perhaps wrinkled in a grin.

Ranger Circle, 2007 by Simon Gush is a slow pan in snapshots that dissolve into each other of man on a horse in the tall grass that reminded me of the more solid memorials on plinths around the world dedicated to those who generally spent their life running down others on horseback with saber and rifle. Struggles of the Heart, by Churchill Madikida shows the artist’s face in close-up, covered in white paint as he shovels handfuls of gruel into his mouth. At some point it became apparent that the film was playing in reverse, or had it always been? As he slurps the paste, nearly choking, more of it comes leaping into the frame from below into his mouth. His eyes are pressed tightly closed in concentration and perhaps wrinkled in a grin.

Hit play, and suddenly you’re navigating between two worlds, as Cardiff’s voice over directs your attention while the view finder shows you another walk through the museum, now juxtaposed against your surroundings. The space around you seems filled with ghosts, revealed only to you through the video. People glide by, invisible to the other visitors and you notice details like artwork that has changed or been removed. There is a disorienting feeling as you match your movements to hers, and the strange sense that you’re inhabiting someone else’s body: that you should recognize the people she singles out, that you should remember relationships hinted at. You begin to rely on her cues so much that at one point when the screen goes black, it’s as if Cardiff has abandoned you and there is something like a feeling of betrayal.

Hit play, and suddenly you’re navigating between two worlds, as Cardiff’s voice over directs your attention while the view finder shows you another walk through the museum, now juxtaposed against your surroundings. The space around you seems filled with ghosts, revealed only to you through the video. People glide by, invisible to the other visitors and you notice details like artwork that has changed or been removed. There is a disorienting feeling as you match your movements to hers, and the strange sense that you’re inhabiting someone else’s body: that you should recognize the people she singles out, that you should remember relationships hinted at. You begin to rely on her cues so much that at one point when the screen goes black, it’s as if Cardiff has abandoned you and there is something like a feeling of betrayal.